Historical Research

(2002 - 2016)

NOTE: Work-in-progress. Please check back as more material is added once permissions have been granted from various institutions.

This section includes related research and ephemera of historical significance that directly informed the making of the project Through Darkness to Light: Photographs Along the Underground Railroad, such as: facsimiles of newspaper ads, society minutes, academic papers, in addition to quotes and accounts from participants in the Underground Railroad. Where available, images from the various collections used to piece together the route are shown. As well as, information that explains specific locations, stops, and/or people all organized according to the documented route. Overarching ephemera is presented at the beginning of this page. Below is where ephemera specific to the route is shown. The epigraphs add Underground Railroad participant's voices to the journey and include well-known figures as well as local people.

The Underground Railroad operated in opposition to the law. The first Fugitive Slave Law was passed in 1793 providing for the return of enslaved blacks who had escaped and crossed state boundaries. A second stronger law was passed as part of the Missouri Compromise in 1850.

Map of Underground Railroad routes from 1830 - 1865. Compiled from The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom by Wilbur H. Siebert, 1898.

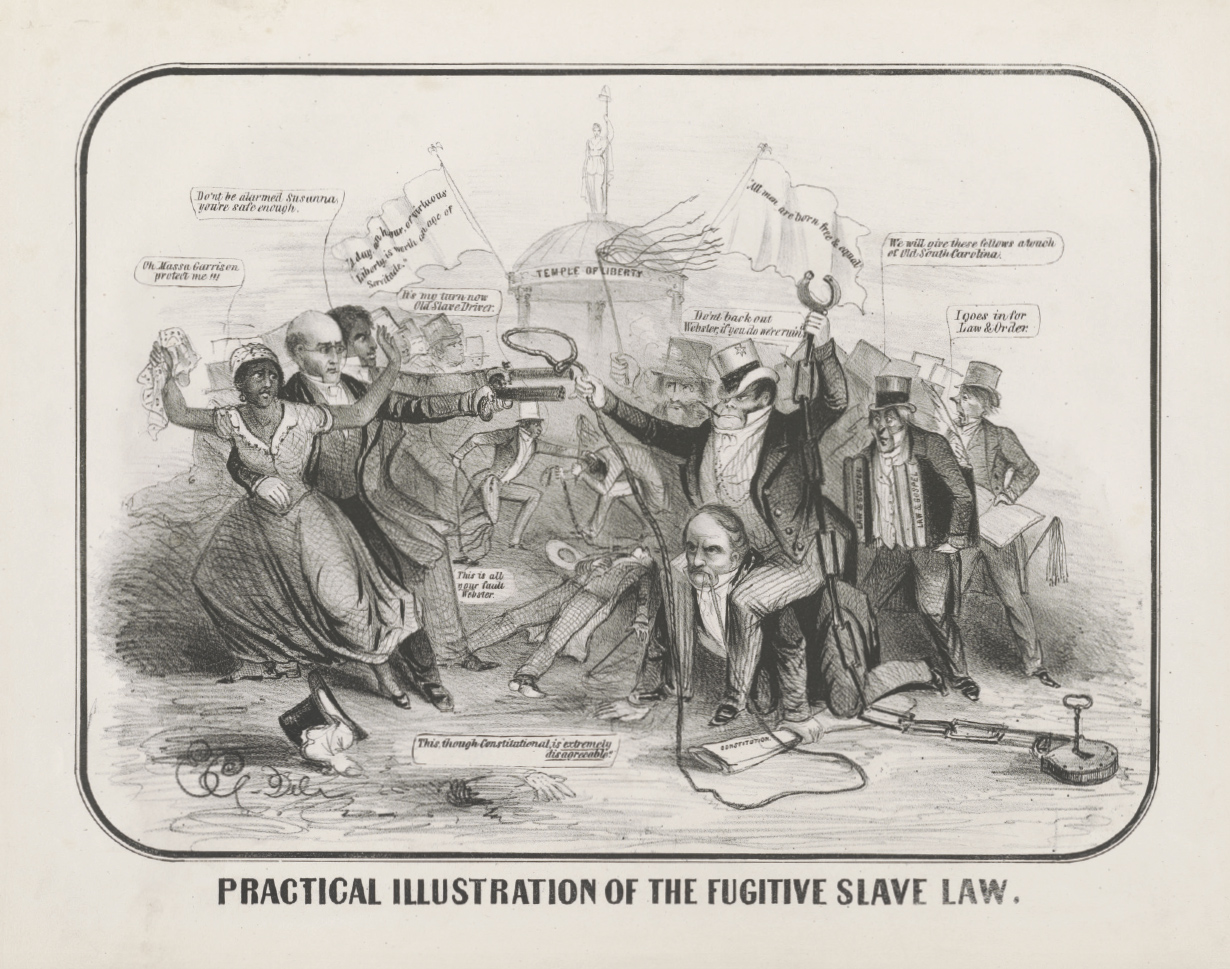

Practical Illustration of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1851, a satirical cartoon capturing the hostility between Northern abolitionists, portrayed on the left, and supporters of the Fugitive Slave Act, on the right, including Secretary of State Daniel Webster, who bears a slave catcher on his back. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Front of Signed Underground Railroad Pledge. Indiana Historical Society, M0199

Back of Signed Underground Railroad Pledge has a code and the signature of J. Pearce. Indiana Historical Society, M0199

Frederick Douglass stated that he could “think no better exposure of slavery can be made than is made by the laws of the states in which slavery exists.”

“If more than seven slaves together are found in any road without a white person, twenty lashes a piece; for visiting a plantation without a written pass, ten lashes; for letting loose a boat from where it is made fast, thirty-nine lashes for the first offense; and for the second, shall have cut off from his head one ear; for keeping or carrying a club, thirty-nine lashes; for having any article for sale, without a ticket from his master, ten lashes; for traveling in any other than the most usual and accustomed road, when going alone to any place, forty lashes; for traveling in the night without a pass, forty lashes.’ He further states, “I am afraid you do not understand the awful character of these lashes. You must bring it before your mind. A human being in a perfect state of nudity, tied hand and foot to a stake, and a strong man standing behind with a heavy whip, knotted at the end, each blow cutting into the flesh, and leaving the warm blood dripping to the feet, and for these trifles.” ‘For being found in another person’s negro-quarters, forty lashes; for hunting with dogs in the woods, thirty lashes; for being on horseback without the written permission of his master, twenty-five lashes; for riding or going abroad in the night, or riding horses in the day time, without leave, a slave may be whipped, cropped, or branded in the cheek with the letter R, or otherwise punished, such punishment not extending to life, or so as to render him unfit for labor.”

[top] Manifest of a slave ship sailing from Richmond, Virginia, to New Orleans, October 18, 1840. African American Resource Center, New Orleans Public Library.

[bottom]

Slaves picking cotton in South Carolina, c. 1860. Rob Oechsle Collection.

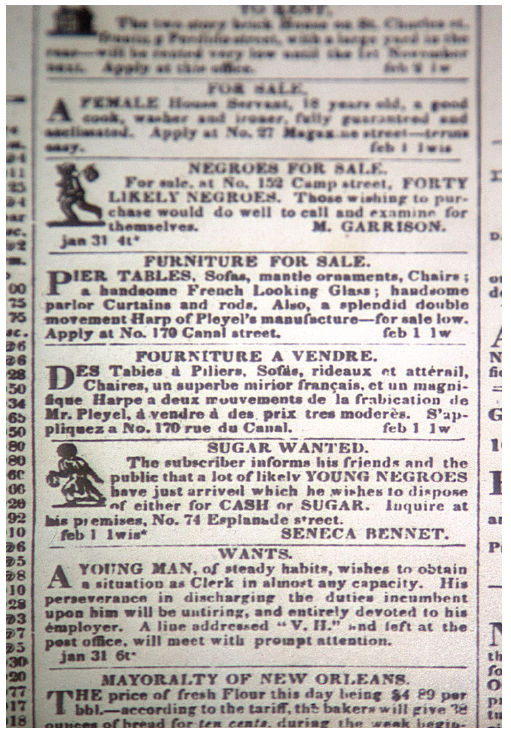

Advertisement offering slaves in exchange for cash or sugar in The Daily Picayune, February 4, 1840. Louisiana Division/City Archives, New Orleans Public Library.

Advertisement announcing “Negroes for Sale” and listing their trades in The Daily Picayune, February 5, 1840. Louisiana Division/City Archives, New Orleans Public Library.

1,400 mile documented route from the project Through Darkness to Light. It covers seven states from Louisiana to Michigan and then on into Canada. A journey that would have taken roughly three months to complete.

Through Darkness.

2014

“They worked me all de day, Widout one cent of pay;

So I took my flight in the middle ob de night,

When de moon am gone away.”

Reason to Leave.

Chorus of a song from abolitionist George W. Clark’s The Liberty Minstrel (1844), 2014

“No man can tell the intense agony which was felt by the slave, when wavering on the point of making his escape. All that he has is at stake; and even that which he has not, is at stake, also. The life which he has, may be lost, and the liberty which he seeks, may not be granted.”

Decision to Leave.

Magnolia Plantation on the Cane River, Louisiana, 2013

The land on which Magnolia Plantation stands was originally acquired by Jean Baptiste LeComte I in 1753. At the height of their prosperity in 1860, the family produced more cotton than anyone else in the Natchitoches Parish. During its prime, it is likely that at least 75 people lived at Magnolia. All of the slave cabins at Magnolia were placed in rows, creating a structured village atmosphere. As with many other plantations in the area, Magnolia’s slave cabins were turned into sharecropper cabins after Emancipation.

Magnolia Plantation survey, 1850s. Courtesy of the LeComte/Hertzog family and the Cane River National Heritage Area.

Historic American Buildings Survey, C., Cizek, E. D. & Tulane University, S. O. A. (1933) Magnolia Plantation, Slave Quarters, LA Route 119, Natchitoches, Natchitoches Parish, LA. Louisiana Natchitoches Natchitoches Parish, 1933. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Tin type of the cotton gin invented by Eli Whitney in 1793, Magnolia Plantation, 2014, Jeanine Michna-Bales. The yield of raw cotton doubled each decade after 1800. Thereby fueling the growth of slavery. While it was true that the cotton gin reduced the labor of removing seeds, it did not reduce the need for slaves to grow and pick the cotton. Cotton growing became so profitable for the planters that it greatly increased their demand for both land and slave labor. In 1790 there were six slave states; in 1860 there were 15.

On the Run.

North of the Cane River Plantations, Louisiana, 2013

“Run, Mary, run; Oh, run Mary, run:

I know the other world is not like this.”

Advertisements offering rewards for the recapture of runaway slaves in the New Orleans Bee, November 16, 1833. Louisiana Division/City Archives, New Orleans Public Library.

Wading Prior to Blackness.

Grant Parish, Louisiana, 2014

Southern Pine Forest.

Following El Camino Real, LaSalle Parish, Louisiana, 2014

Catching a Breath.

LaSalle Parish, Louisiana, 2014

Black River Crossing.

Continuing along El Camino Real, Catahoula Parish, Louisiana, 2014

Stopover.

Frogmore Plantation, Concordia Parish, Louisiana, 2014

“’Tisn’t he who has stood and looked on that can tell you what slavery is—’tis he who has endured.”

Many slave narratives and first-person accounts of escape reference running away to neighboring plantations. Wallace Turnage went to several neighboring plantations before he was able to finally gain his freedom.

Bog.

Catahoula Parish, Louisiana, 2014

Gathering Provisions.

Outskirts of the Myrtle Grove Plantation, Tensas Parish, Louisiana, 2014

Moonlight Over the Mississippi.

Tensas Parish, Louisiana, 2014

“Brothers and sisters we were by blood; but slavery had made us strangers. I heard the words brother and sister, and knew they must mean something; but slavery robbed these terms of their true meaning.”

Through the Forest.

Jefferson County, Mississippi, 2014

Resting Place.

Church Hill, Mississippi, 2015

Hiding Out Back.

Slave cemetery, Mount Locust Stand and Plantation, Jefferson County, Mississippi, 2014

Sunken Trace.

Claiborne County, Mississippi, 2015

Avoiding the Coyotes.

Hinds County, Mississippi, 2014

Determining True North in the Rain.

Along the southern part of the Old Natchez Trace, Mississippi, 2014

“A local grocer heard that the Smiths were mistreating their slaves. He showed Cummings a map of Lake Erie, spoke with him about Ohio and Indiana, taught him to find the North Star and determine direction by moss on the tree, and encouraged him to make a run for it. In July 1839, Cummings fled.”

Tracking the Deer.

Skirting the Osburn Stand, Mississippi, 2014

Cypress Swamp.

Middle Mississippi, 2014

“The conveyance most used on the southern section is known as the “Foot and Walker Line,” the passengers running their own trains, steering by the North Star, and swimming rivers when no boat could be borrowed. ”

Off the Beaten Path.

Along the Yockanookany River, Mississippi, 2014

Following the Trace North.

Attala County, Mississippi, 2014

Doubling Back.

Webster County, Mississippi, 2015

“Now these dogs bit me all over while some of them had hold of my legs the others was biting on my arms, hands and throat. I could not fall for while some of them would pull me one way, the rest would pull me the other way. He made them bite me four or five minutes. Now these hounds was so trained to bite without tearing the f lesh, any one might think after biting four or five minutes and seven of them at that, that they would have torned the f lesh to pieces, but they would not tear the f lesh out. So when he thought that they had bitten me enough, he made them stop and then he asked me who did I belong to. I told him.”

From Whence We Came.

Following Robinson Road, Mississippi, 2014

Stopping for Directions.

Meadow Woods Plantation, Oktibbeha, Mississippi, 2014

Crawling Ahead.

Chickasaw County, Mississippi, 2014

Crossing Open Space.

Lee County, Mississippi, 2014

Keep Going.

Crossing the Tennessee River, Colbert County, Alabama, 2014

“A keen observer might have detected in our repeated singing of “O Canaan, sweet Canaan I am bound for the land of Canaan,” something more than a hope of reaching heaven. We meant to reach the North and the North was our Canaan.”

Through the Underbrush.

Along the Old Natchez Trace, southern Tennessee, 2012

“It would be interesting to follow this heroic girl through her long, lonely journey through Alabama, Tennessee, and Kentucky to the Ohio River, sometimes camping in woods and swamps in the daytime and traveling by the North Star in the night, occasionally finding a resting place in a negro’s cabin, hungry, weary and footsore. ”

Downed Tree.

Wayne County, Tennessee, 2014

Twisted Thicket.

Lawrence County, Tennessee, 2014

Devil’s Backbone.

Lewis County, Tennessee, 2014

Shelter from the Storm.

Hickman County, Tennessee, 2014

“The man I called “Master” was my half brother. My mother was a better woman than his, and I was the smartest boy of the two, but while he had a right smart chance at school, I was whipped if I asked the name of the letters that spell the name of the God that made us both of one blood. ”

Tennessee Valley Divide.

Williamson County, Tennessee, 2014

Taking to the Hollow.

Davidson County, Tennessee, 2014

Hidden in Plain Sight.

Rose Mont Plantation, Sumner County, Tennessee, 2014

Josephus Conn Guild, a prominent Tennessee attorney and owner of the Rose Mont Plantation, represented twenty-four slaves who were granted manumission in their master’s will, but were denied freedom by the executor of the estate. On January 26, 1846, the Tennessee Supreme Court upheld their right to be free.

A Lesson in Astronomy.

Southern Kentucky, 2014

“Where Moses (he said they called him Mose) lived, the slaves were partially educated. Their mothers taught them a short lesson in astronomy, namely, the position of the North Star and how to find it. ”

Fleeing the Torches.

Warren County, Kentucky, 2014

“I had reasoned this out in my mind; there was one of two things I had a right to, liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other; for no man should take me alive; I should fight for my liberty as long as strength lasted, and when the time came for me to go, the Lord would let them take me.”

Hidden Passage.

Mammoth Cave, Barren County, Kentucky, 2014

Documents show that “passengers” of the Underground Railroad passed through the cities surrounding Mammoth Cave, including Cave City, Glasgow, and Munfordville, where they could safely cross the Green River. While there is no evidence that the cave itself was used by the Underground Railroad, the most accurate map of the cave system was drawn in the 1842 by Stephen Bishop, an enslaved black and cave guide who gave tours to travelers. The map was published in 1845 by Morton & Griswold Publishers and was still being utilized as the main source of reference for the cave in 1887.

Following the Green River.

Edmonson County, Kentucky, 2014

Secret Tunnels.

Munfordville Presbyterian Church, Munfordville, Kentucky, 2014

Old Man Moon.

Hardin County, Kentucky, 2014

Into the Night.

Spencer County, Kentucky, 2014

Racing the Stars.

Between Oldham and Shelby Counties, Kentucky, 2014

Over the Hills.

North Trimble County, Kentucky, 2014

The River Jordan.

First view of a free state, crossing the Ohio River to Indiana, 2014

The origin of the term “Underground Railroad” is disputed. Abolitionist Rush Sloane offered an account in 1831, stating that the term originated from an episode in which a fugitive slave, Tice Davids, fled across the Ohio River pursued by his owner. Upon reaching the shore, Davids disappeared, leaving the bewildered slaveholder to wonder if Davids had somehow “gone off on an underground road.” (Ohio History Connection. “Tice Davids.” http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Tice_Davids) Another story states that the term came into use among frustrated slave hunters in Pennsylvania, and a third tale, from 1839 in Washington, DC, alleges that a fugitive slave, after being tortured, claimed that he was to have been sent north, where “the railroad ran underground all the way to Boston.” (Robert C. Smedley, History of the Underground Railroad in Chester and the Neighboring Counties of Pennsylvania [Lancaster, Pennsylvania: 1883] quoted in David W. Blight, From Passages to Freedom: The Underground Railroad in History and Memory [Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books in association with the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, 2004], 3.

Eagle Hollow from Hunter’s Bottom.

Just across the Ohio River, Indiana, 2014

At Eagle Hollow, part of a network of Underground Railroad stations that shepherded the enslaved northward through Indiana, Chapman Harris—a free man, reverend, and blacksmith—devised an ingenious mode of communication to notify both other agents and enslaved on the opposite shore of the Ohio River that he or his sons were about to row their skiff across and all who wanted to accompany them back were welcome. Outside his home at Eagle Hollow, three miles east of Madison, Harris placed an iron plate or anvil in the trunk of a sycamore tree; when the time came to go across the Ohio to pick up fugitives, he would hammer on the anvil. [Madison Courier, January 12, 1880]

Dr. Lott’s House.

Georgetown District of Madison, Indiana, 2013

Some communities were thrust into Underground Railroad work due to proximity. One such area was the city of Madison, Indiana that is situated on the Ohio River, the dividing line between the north and the south, just across from Trimble County, Kentucky. The Georgetown District was a free black community that had a few conductors that resided there. One of the most notable of them was George DeBaptiste. He eventually relocated North to Detroit after raids from Kentucky had threatened his life one too many times. Several other routes out of town led from the Ohio River up through Eagle Hollow and Ryker’s Ridge.

Chapman Harris was endangered at least twice during his activities as a pilot. Once, another black, John Simmons, also privy to information about the activities, made the nearly fatal mistake of divulging what he knew. Harris and a fellow black worker, Elijah Anderson, led a group of men who nearly whipped Simmons to death. Apparently the only thing that saved the informer's life was that he bit part of Harris' lip off. On this evidence, a judge of the circuit court in Jefferson County convicted Harris of the beating and fined him several hundred dollars. ["Blacks in and Around Jefferson County," typescript in Jefferson County Library, Madison, Indiana]

Anderson and another black worker, George De Baptiste, were virtually run out of Madison for their work on the Underground Railroad. De Baptiste continued his work in Detroit while Anderson continued his in Toledo, Ohio. Anderson, however, made periodic trips to Kentucky to rescue enslaved blacks. Finally caught and arrested while leading a group of blacks out of Kentucky, Anderson was subsequently sentenced to imprisonment in the Kentucky State Penitentiary at Frankfort where he died, mysteriously. [Madison Courier, June 15, 1874; Elijah Anderson case file, Governor C. S. Morehead Papers, Public Records Division, Frankfort, Kentucky]

Woods on the Way to Wirt.

Jefferson County, Indiana, 2014

“After dark I drove to the place agreed upon to meet in a piece of woods one mile from the town of Wirt. I had been at the appointed place but a very short time when Mr. DeBaptiste sang out, “Here is $10,000 from Hunter’s Bottom tonight.” A good Negro at that time would fetch from $1,000 up. We loaded them in...and started with the cargo of human charges towards the North Star.”

Other Underground Railroad communities possessed such moral authority that the network became a defining characteristic of the area. Such was the case with the Central and Eastern routes that ran through Indiana. The Neil’s Creek Anti-slavery Society, of Jefferson County, had quite a few members that were notable stationmasters, including the Reverend Thomas Hicklin and John H. Tibbets, who wrote of his experiences with the Underground Railroad in his reminiscences. The area included a large African American community of free and enslaved blacks called Africa, morally strong whites who adamantly believed that all people were created equal, a school dedicated to educating people of any color, as well as various religious organizations.

Dr. Samuel Tibbets was a cofounder and trustee of the Eleutherian College in Lancaster, Indiana, which was one of the earliest educational opportunities for women and African-Americans before the Civil War. He was an abolitionist and president of Neil's Creek Anti-Slavery Society, 1839-1845. His son, John Henry Tibbets, was an Underground Railroad conductor. John's document, The Reminiscences of Slavery Times, is a rare first-hand account of his adventures. The Tibbets family brought their underground railroad methods from Clermont County, Ohio, where they cofounded the abolitionist Lindale Baptist Church.

Wade in the Water.

Graham Creek in Jennings County, Indiana, 2013

“Wade in the water,

wade in the water children,

God’s a-going to trouble the water”

On the Way to the Hicklin House Station.

San Jacinto, Indiana, 2013

William and Margaret Hicklin acquired 320 acres in Jennings County Indiana on Little Graham Creek in 1819. Their sons Thomas Hicklin, Lewis Hicklin, John L. Hicklin and James Hicklin lived on this land and operated an outstanding Underground Railroad Station. Lewis and Thomas Hicklin became ministers and John and Martha Hicklin were members of Graham Baptist Church and in 1842 donated two acres of land for the church. James Hicklin was dismissed, from this church for "breaking the law and aiding to convey slaves from their masters". Lewis Hicklin was an agent for the Anti-Slavery Society and started Neil's Creek Anti-Slavery Society of Lancaster, Indiana, and many others. The Hicklin Station was located just ten miles north of Eleutherian College in Lancaster, Indiana. There are documented stories in the William Seibert Papers about the Hicklin Station and their work in moving freedom seekers north to freedom. Wright Rea, the slave catcher of Madison, Indiana, watched the Hicklin Station very closely to try to catch the family in their Railroad activities, but was never successful in that effort. William, wife Margaret and son Thomas Hicklin are buried at Home site, the rest of the family moved to Oregon in 1849.

Thomas Hicklin, an active abolitionist in Jennings County, operated a station one half mile east of San Jacinto and enslaved blacks to another station on Otter Creek in Campbell Township, and to a station at the home of John Vawter. Instead of continuing on, some fugitives remained in a black settlement southwest of Vernon. ["A Glimpse of Pioneer Life in Jennings County," 137, Alice Ann Bundy Collection, Indiana Division, Indiana State Library; Coffin, Reminiscences, 181-82.]

Follow the Tracks to the First Creek.

Just outside Richland, a free black community, Stone Arch Railroad Bridge, Vernon, Indiana, 2013

“Wright Ray, a noted negro catcher... was also sheriff of Jefferson County for many years and used his office for that purpose. [He] was known all over Kentucky and was always applied to when a slave got away.”

Follow the Drinking Gourd.

Jefferson County, Indiana, 2013

“For the old man is a-waiting

for to carry you to freedom.

If you follow the drinking gourd.”

Some scholars believe that the signature line in the chorus of “Follow the Drinking Gourd” is not original and attribute it to Lee Hays, who published it eighty years after the end of the Civil War. According to other accounts, however, this chorus was heard as early as the 1840s.

Elias Conwell House.

Along Old Michigan Road, a major north-south artery between Kentucky and Michigan, Napoleon, Indiana, 2013

The Michigan Road ran from Madison to northern Indiana and, once there, the fugitives may have taken the Chicago to Detroit trace to either Illinois or Michigan. Following the Michigan Road from Madison to South Bend or Michigan City, the fugitives and conductors could also have veered off to La Porte, the "door" to the prairie, or to the northeast and Detroit.

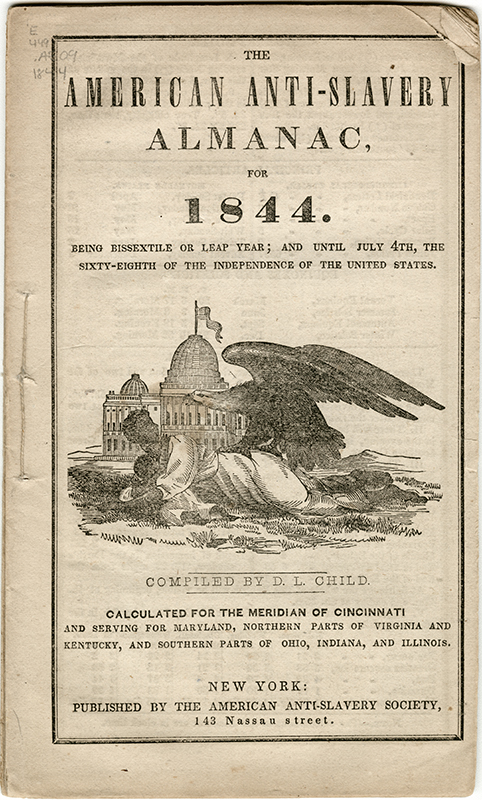

Cover of the American Anti-Slavery Almanac, 1844. Indiana Historical Society.

Moonrise Over Northern Ripley County.

From the Decatur County line, Indiana, 2013

Nightlight.

Passing into Fayette County, Indiana, 2014

Friend or Foe?

Station just outside Metamora, Indiana, 2014

Nearing Brookville.

Franklin County, Indiana, 2014

A Brief Respite.

Abolitionist William Beard’s house, Union County, Indiana, 2014

Also from Madison, Indiana, enslaved blacks could travel to Brooksburg, Marble Hill, or Vevay, but the next main stop was in Union County at the home of abolitionist William Beard, of Salem in Union County. Beard was just as active as Levi Coffin in Newport. Members of the Henry County Female Anti-Slavery Society took up donations to buy 127 yards of free-labor cotton in order to sew garments: vests, coats, pants, dresses, shirts, and socks. Two-thirds of the garments were directed to Salem, Union County, care of William Beard. Apparently Beard forwarded many of the reputed 2,000 enslaved blacks Coffin is said to have sent to Canada. From Union County the self-emancipated slaves might go to various points in Decatur, Dearborn, Rush, Henry, and Wayne counties. [Henry County Female Anti-Slavery Society minutes, Indiana Division, Indiana State Library.]

Go to the House on the Hill.

Possible Underground Railroad station, Cambridge City, Indiana, 2013

Look for the Gray Barn Out Back.

Joshua Eliason Jr. barnyards and farmhouse, with a tunnel leading underneath the road to another station, Centerville, Indiana, 2013

The current occupants of the former farmhouse and barn verify the existence of a tunnel connecting the two properties. It was sealed long ago.

A Very Good Road.

Drawing near the Bishop Paul Quinn Station, Richmond, Indiana, 2014

A Safe Place to Regroup.

House of Levi Coffin, who was unofficially dubbed the president of the Underground Railroad, Fountain City (formerly Newport), Indiana, 2014

The Underground Railroad was a loosely organized network whose participants had no titles, but friends and supporters of Levi Coffin—who, with his wife, Catherine, was an important organizer and abolitionist over four decades—referred to him as “president.” And their home became known as "The Grand Central Station of the Underground Railroad."

“The dictates of humanity came in opposition to the law of the land, and we ignored the law.”

Many of the Quakers of Indiana came from North Carolina and Tennessee and witnessed first-hand the atrocities of slavery. Including Levi Coffin and other members of his family who settled in and around Newport (now Fountain City), Indiana. They formed an Anti-Slavery Society and were regular contributors to the newspaper The Free Labor Advocate which championed immediate emancipation of all slaves, as well as only purchasing goods and produce that did not involve slave labor. Levi and Catharine Coffin were adamant supporters of the Underground Railroad while in Indiana and continued to support it after their move to Cincinnati, Ohio. The Levi Coffin Home is a National Historic Landmark and is now a part of the Levi Coffin Indiana State Museum Historic Site.

Levi and Catharine Coffin were Quakers from North Carolina who opposed slavery and became very active with the Underground Railroad in Indiana. During the 20 years they lived in Newport, they worked to provide transportation, shelter, food and clothing for hundreds of freedom seekers. Many of their stories are told in Levi Coffin’s 1876 memoir, Reminiscences.

Their eight-room house was the third home of Levi and Catharine Coffin in Newport, and it was a safe haven for hundreds of enslaved blacks on their journey to Canada. Levi and Catharine Coffin’s home became known as “The Grand Central Station of the Underground Railroad.” The Coffins and others who worked on this special “railroad” were defying federal laws of the time.

From the outside it looks like a normal, beautifully-restored, Federal-style brick home built in 1839. Being a Quaker home, the Coffin house would not have had many of the era’s decorative features such as narrow columns, delicate beading or dentil trim. On the inside, however, it has some unusual features that served an important purpose in American history. Most rooms in the home have at least two ways out, there is a spring-fed well in the basement for easy access to water, plenty of room upstairs allowed for extra visitors, and large attic and storage garrets on the side of the rear room made for convenient hiding places. The location of the house, on Highway 27 at the center of an abolitionist Quaker community, allowed the entire community to act as lookouts for the Coffins and give them plenty of warning when bounty hunters came into town.

For their journey north, freedom seekers often used three main routes to cross from slavery to freedom — through Madison or Jeffersonville in Indiana, or Cincinnati, OH. From these points, slaves traveled to Newport through the Underground Railroad. The Coffins’ “station” was so successful that every enslaved person who passed through eventually reached freedom.

Cover of The Free Labor Advocate and Anti-Slavery Chronicle, 1842. Friends Collection, Lilly Library, Earlham College.

Advertisement for Levi Coffin’s store promising “free labor dry goods and groceries” in the Free Labor Advocate, and Anti-Slavery Chronicle, July 1, 1847. Friends Collection, Lilly Library, Earlham College.

Advertisement outlining the aims of the North Star, an anti-slavery weekly proposed by Frederick Douglass, in the Free Labor Advocate, and Anti-Slavery Chronicle, September 30, 1847. Friends Collection, Lilly Library, Earlham College.

Approaching the Seminary.

Near Spartanburg, Indiana, 2014

“Differences in government, discipline, and privileges will not be made with regard to color, rank, or wealth.”

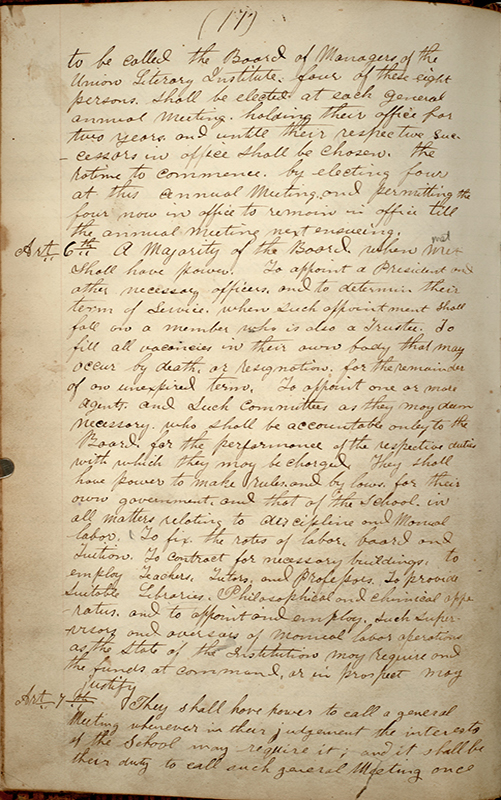

Union Literary Institute was one of the first schools to offer higher education without regard to color or sex before the Civil War. It was established in 1846 by a biracial board, including free blacks from nearby settlements. At the time, Indiana laws did not allow blacks to attend the public schools. Students labored four hours a day in exchange for room and board.

The school was supported by local and national donations, including land. Ebenezer Tucker was the first teacher, and notable attendees included Hiram Revels, the first black U.S. Senator, and James S. Hinton, the first black elected to the Indiana House of Representatives. In 1860 a two-story brick structure was built. The school was a noted Underground Railroad stop.

Union Literary Institute Constitution from the Board of Managers’ Secretary Book. BV1972_016-018, Indiana Historical Society.

Taking Cover with the Fireflies.

North of Winchester, Indiana, 2014

On the Safest Route.

James and Rachel Sillivan cabin, Pennville (formerly Camden), Indiana, 2014

Several documents from the mid-1800s to the present indicate that Eliza Harris stayed at this location during her flight northward. Her crossing of the Ohio River would become one of the best known escapes due to her representation in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

A.S. Seer Print. Uncle Tom's cabin. , 1882. [N.Y.: A.S. Seer's Print]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington D.C.

Orange Moon.

Adams County, Indiana, 2014

Walk Along the Ridge.

Between the Maumee and St. Joseph Rivers, Braun-Leslie House, Fort Wayne, Indiana, 2014

Wayne County had many contributors to the Underground Railroad effort. Apparently by the 1850s Wayne County conductors and agents formed a Society of Underground Railroad workers, with a membership pledge and code. From Richmond, but mainly from Newport, conductors took enslaved blacks through Randolph and Jay counties to points east and west. In the east, splinter lines ran through Winchester, Marion, and Bluffton to Fort Wayne, then to Toledo, Ohio, and on to Canada. An alternative route was through Winchester, Marion, the Wabash-Huntington area, and Logansport. Addison Coffin, a transporter on the "line," wrote in 1844, "The Wabash line was in good running order and passengers very frequent." [Underground Railroad pledge with signature of J. Pease, Thomas Marshall Collection, Indiana Historical Society Library and Addison Coffin, Life and Travels of Addison Coffin (Cleveland, 1897), 88-89]

Lying Low.

William Cornell House, outside Auburn, Indiana, 2014

Queen Anne’s Lace.

South Steuben County, Indiana, 2014

Bird’s Eye View.

Erastus Farnham House, south of Fremont, Indiana, 2014

Dirt Road.

Outside Coldwater, Michigan, 2014

Concealed in the Fog.

Near Jonesville, Michigan, 2014

Nearing the Farm.

Royal Watkins farmstead, Jackson County, Michigan, 2014

“Liberty to the Fugitive Captive.”

Waiting for the all-clear to head to the Captain John Lowry Station, Lodi Plains Cemetery, Nutting’s Corner, Michigan, 2014

“Liberty to the fugitive captive and the oppressed over all the earth, both male and female of all colors.”

Sylvia and Captain John Lowry boldly invited freedom seekers to their home via a large board sign that was above the gate to their yard. It was painted with two figures, one white and the other black, holding a scroll between them. Their daughter, Mary E., described the sign: “The figure at the right is a female form, with heavy chain in the left hand, but broken are the links. In her right hand she holds the balances. To the left, and in the act of rising, is the figure of a man of darker hue … but, clad in freeman’s garb; while around one wrist is clasped the other end of slavery’s chain, with many missing links, and to his sister he looks up for help and perfect freedom, their faces all aglow with triumph, and just below appears this motto: ‘liberty to the fugitive captive and the oppressed over all the earth, both male and female of all colors.’” Carol E. Mull, The Underground Railroad in Michigan (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Publishers, 2010), 94.

Moon Over the “Old Slave House.”

Reverend Guy Beckley’s home north of the Huron River, Lower Town, Michigan, 2014

Delayed Arrival.

Arthur and Nathan Power Station, Quakertown, Michigan, 2014

Wait for the Call of the Hoot Owl.

Oakland County, Michigan, 2014

The Beacon Tree.

Spring Hill Farm, Macomb County, Michigan, 2014

A composite of photographs from two different locations, this image represents a memory described by Liberetta, the daughter of Peter and Sarah Lerich. As a five-year-old, Liberetta witnessed her parents and their neighbors John Narramoor, John Waters, and Mr. and Mrs. Fuller uprooting a massive cedar and pulling the tree—with three yoke of oxen—to the top of a hill, where they replanted it. Gathering near the tree, the group prayed for their “black brethren” and the “down-trodden race” and sprinkled newspaper clippings of the National Era on the cedar’s roots. Mrs. Narramoor soon arrived, announcing that the tree was visible a mile away.

A Place of Rest.

Rufus Nutting House, Romeo, Michigan, 2014

Scrub Field.

Leaving Reverend Oren Cook Thompson Station, St. Clair County,

Michigan, 2014

Within Reach.

Crossing the St. Clair River to Canada just south of Port Huron, Michigan, 2014

“Slaves cannot breathe in England [and Canada]: if their lungs

Receive our air, that moment they are free;

They touch our country, and their shackles fall. ”

Freedom.

Canadian soil, Sarnia, Ontario, 2014

“I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person now I was free. There was such a glory over everything, the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in heaven.”

By the 1850's there were six 'firmly rooted' black communities in Ontario, Canada. These communities served as havens for enslaved blacks prior to the Civil War.

1. Central Ontario (London, Queen's Bush, Brantford, Wilberforce)

2. Chatham (Dawn, Elgin)

3. Detroit Frontier (Amherstburgh, Sandwich, Windsor)

4. Niagara Peninsula (St. Catharine's, Niagara Falls, Newark, Fort Erie)

5. Northern Simcoe & Grey Counties (Oro, Collingwood, Owen Sound)

6. Urban Centers on Lake Ontario (Hamilton, Toronto)

Buxton (Elgin) Settlement 1849, now the Buxton National Historic Site & Museum- The Elgin Settlement, also known as Buxton, was one of four organized black settlements to be developed in Canada. The black population of Canada West and Chatham was already high due to the area's proximity to the United States. The land was purchased by the Elgin Association through the Presbyterian Synod for creating a settlement. The land lay twelve miles south of Chatham. The Reverend William King believed that blacks could function successfully in a working society if given the same educational opportunities as white children. "Blacks are intellectually capable of absorbing classical and abstract matters.” Being a reverend and teacher, the building of a school and church in the settlement was a necessity to him. The settlement also was home to the logging industry. George Brown, who later became one of the Fathers of Confederation, was a supporter of William King and helped build the settlement.

Emancipation Proclamation broadside, 1864. The Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

EPIGRAPH SOURCES

Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (New York: Dover Publications, 1995), 9.

Frederick Douglass and David W. Blight, My Bondage and My Freedom (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014), 226.

Eber M. Pettit, Sketches in the History of the Underground Railroad (Westfield, NY: Chautauqua Region Press, 1999), 31.

“Run, Mary, Run” in James Weldon Johnson, J. Rosamond Johnson, and Lawrence Brown, The Books of American Negro Spirituals (New York: Da Capo Press, 2003), 110.

Federal Writers’ Project, Tennessee Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in Tennessee from Interviews with Former Slaves (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 2006), cover.

Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom, 41.

Jacob Cummings, “Interview with Reverend Jacob Cummings, an Escaped Slave Living in Columbus, Ohio” in The Underground Railroad in Indiana, vol. 1, ed. Wilbur H. Siebert, Wilbur H. Siebert Collection, Ohio Historical Society.

Pettit, Sketches in the History of the Underground Railroad, 128.

David W. Blight, A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom: Including Their Own Narratives of Emancipation (Boston: Mariner Books, 2007), 243.

Frederick Douglass, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2003), 109.

Pettit, Sketches in the History of the Underground Railroad, 118.

Pettit, Sketches in the History of the Underground Railroad, 96.

Pettit, Sketches in the History of the Underground Railroad, 114.

Sarah Bradford, Harriet, the Moses of Her People (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 17–18.

John H. Tibbets, Reminiscences of Slavery Times, unpublished chronicle, 1888, collection of Eluetherian College, Inc., Lancaster, Indiana.

Bordewich, Bound for Canaan, 64.

Union Literary Institute Minutes Book, 1845–1890, Indiana Historical Society, BV1972, 18.

Tibbets, Reminiscences of Slavery Times.

Carol E. Mull, The Underground Railroad in Michigan (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Publishers, 2010), 94.

William Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom; or, The Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery (London: Aeterna Publishing, 2010), i.

National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, Underground Railroad (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 2005), 44.

![[top] Manifest of a slave ship sailing from Richmond, Virginia, to New Orleans, October 18, 1840. African American Resource Center, New Orleans Public Library.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ab0037d5b409b60dd6390bb/1524758206520-5C0IZXEVLXLTVF2EUOQ1/SlaveShipManifest_1.jpg)

![[bottom]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ab0037d5b409b60dd6390bb/1524758368215-XDSCJ5NAM973RV5F3CPF/SlaveShipManifest_2.jpg)

![A.S. Seer Print. Uncle Tom's cabin. , 1882. [N.Y.: A.S. Seer's Print]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington D.C.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ab0037d5b409b60dd6390bb/1524786399391-0SKQ7VIH3W2MIPECKCEB/UncleTom%27sCabin.jpg)